Once declared a vagrant by a magistrate, the person would be taken into custody and would begin their journey back ‘home’. Home in this context meant the parish where they held legal settlement, which in many cases was where they (or their father/husband) was born, but may also have been the last place where they managed to secure employment for twelve consecutive months, or where they rented a property worth at least £10 p.a.

Each county had their own perogative for how they wanted to administer this system. As David Hitchcock noted, the idea of a vagrant contractor was established in the early eighteenth century, possibly in Warwickshire in 1709 when the local constables handed over responsibility for conveying vagrants to a man named Will Wright who did the job on behalf of the whole county; a reaction to the Vagrancy Cost Removal Act of 1700.[2]

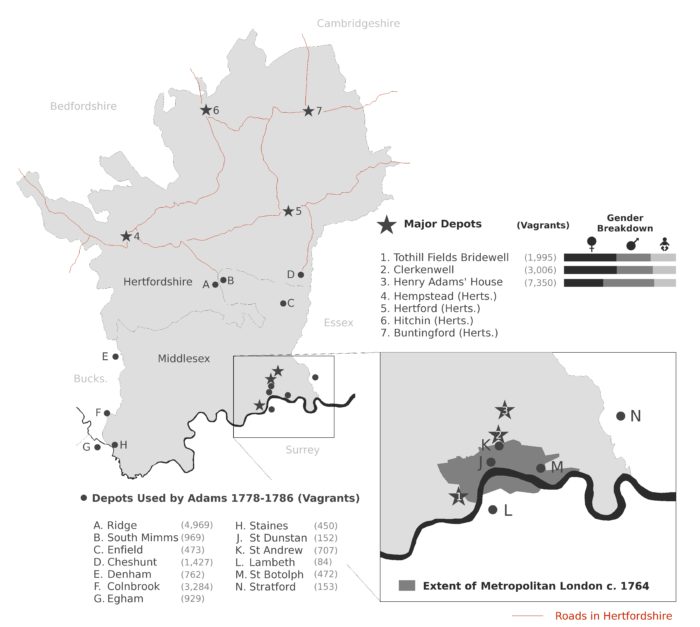

As this network of contractors grew, so too did the need for coordination. A contractor from Middlesex needed to know he could leavea a vagrant at the border of the next county and that someone would be there to take possession of the person for the next leg of the journey. The series of depots used in Middlesex has been well charted by myself and my colleagues: Louise Falcini &Tim Hitchcock.[1] But the rest of the country is less well understood in this regard.

That’s why I was so pleased to discover that David Hitchcock’s book contained detail of the depots used in Hertfordshire (immediately north of Middlesex), allowing us to get a clearer picture of how these waypoints come together, which you can see combined with our earlier work in Figure 1.[3][4]

This is exciting (for me) because it highlights a clear attempt to build an efficient and geographically strategic network of administration. Like strategically placed medieval forts were erected for defence against invaders, these depots have been placed to ensure people are shepherded through as efficiently as possible.

In the case of Hertfordshire, there is also a clear sense that they’re merely handling vagrants expelled from Middlesex. Hertfordshire’s most busy depot (according to David Hitchcock) is Hempstead in the west, handling three-times more vagrants than Hertford in the east. You’ll note from Figure 1, that 3:1 ratio is roughly the same proportion of business going through Ridge (the logical depot on the way to Hempstead) and Cheshunt (the logical depot on the way to Hertford). Despite the fact that David Hitchcock’s research pertains to the period 1700-1750 whereas ours looks at c., 1775-1785 there’s a clear sense of well-worn paths and reasonably consistent flows of people out of Middlesex.

I would love to continue charting this network across the country, so if you have records for other counties, please get in touch.

Footnotes:

- Tim Hitchcock, Adam Crymble, & Louise Falcini, ‘Loose, idle and disorderly: vagrant removal in late eighteenth-century Middlesex’, Social History vol .39, no. 4 (2014).

- David Hitchcock, Vagrancy in English Culture and Society, 1650-1750 (2016), 109.

- David Hitchcock, Vagrancy in English Culture and Society, 1650-1750 (2016), 120.

- With thanks to Louise Falcini: QS/MISC/B/133/1-4 in Herts RO contains the Justices Orders to Masters of Houses of Correction regarding the maintenance and conveyance of vagrants, showing amounts allowed in each case.