![Carington Bowles, 'Irish Peg in a rage. Make good the damage you dog, or I'll cut away your parsnip' (1773) [Trustees of the British Museum]](http://www.migrants.adamcrymble.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IrishPeg.jpg)

I wouldn’t jump to too quickly label this an anti-Irish caricature. I say that because, though it certainly doesn’t depict Peg (or the young man) in an overly flattering light, the print was produced by Carington Bowles, a London-based third-generation print seller known for his satyrical engravings of social interaction in Georgian London[2]. For Bowles, just about anyone was fair game, including the English of all social classes. In that sense, he hasn’t singled out the Irish for scorn; rather he has included them in his ongoing attempts to document life in London. In so doing he’s implicitly acknowledging the Irish as part of his city. It’s a few inches towards acceptance, if not as far as we might hope (from Peg’s point of view).

The image paints Peg as a hard woman who has been forced to look out for herself on the London streets. She seemingly cannot trust the man to compensate her, so she takes matters quite literally into her own hands. Her plight is contrasted sharply by the obviously comfortable circumstances of the Englishman. For a contemporary, his sharp dress, cleanliness and outward appearance of health would signal that he has servants at home to buy and cook any cauliflowers he will consume. Under normal circumstances there is therefore no need for him to speak to, let alone acknowledge Peg. Presumably Peg will be cooking her own cauliflower.

In that sense, what we see is a juxtaposition from a Londoner’s point of view of immigrant and local experience. It’s a juxtaposition that probably contains more than a grain of truth to it. I suspect this Irish Peg was a real woman, probably known casually to the engraver. At the least she is a caricature of one of the many feisty hawkers who made a living selling on London’s streets in the eighteenth century and who had to take care of themselves. However, if Peg was real, I’ve yet to come across any written evidence to prove it. No ‘Irish Pegs’ fit the description in London in the 1770s.

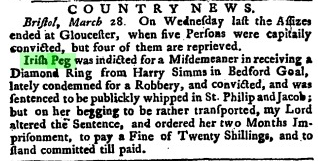

But there are other Irish Pegs. Margaret Eaton, who went by the name ‘Irish Peg’, was a notorious thief in the city’s east end in the 1730s [3], and another named Margaret Poland who too used the moniker in the 1740s[4]. In 1747, another Irish Peg was arrested in Bedford for receiving a stolen diamond (Figure 2)[5]. And in 1815, an Irish Eliza appears in the Proceedings of the Old Bailey in which a witness describes a fight between the woman and a friend over a torn dress[6].

Nicknames are a funny business. At least one witness seems unaware of the woman’s real name, suggesting he had only ever known her by her alias. But one can never be sure if a nickname was self applied, or adopted begrudgingly after repeated use. With these Irish Peg’s and Eliza’s, one gets the sense that they were names the women were happy enough to respond to.

All of these Pegs are almost certainly Irish immigrants, and yet the name implies people who were not Irish spoke to her, and addressed her by name. That in itself is a big step in a lonely city. We can infer that the nickname came from an English tongue, for the same reason we don’t see anyone named ‘English William’ on the city’s streets. If there were an ‘English William’, we’d more likely find him in Dublin than in London where the adjective was a distinguishing feature rather than a reflection of the collective. If Peg did get her name from a English person, that means that English people took the time to talk to Peg, probably more than once. They learned enough about her to know she was Irish and that her name was Peg. But they went further than just learning her name, because they found a way to categorise her and fit her mentally into their neighbourhood. Presumably there was more than one Peg nearby, because they had to find a way to disambiguate this Peg from someone else, to make sure everyone knew who they meant. Why else would anyone make someone’s name longer than it needed to be?

These are baby steps towards integration. And though all of the Irish Peg’s I’ve mentioned appear to have lived on the margins of society, her name tells us that she was finding a place. As Janice Turner notes, one Irish Peg (Margaret Eaton, described above) even managed to infiltrate the East London underworld, to the extent that thief takers were willing to defend her in court, keeping her out of prison on at least one occasion[7]. Perhaps not the type of integration locals might hope for in an immigrant, but for me, the name ‘Irish’ Peg suggests a level of endearment, and an early step in the process towards community acceptance.

Notes:

- Carington Bowles, ‘Irish Peg in a rage. Make good the damage you dog, or I’ll cut away your parsnip’ (1773) [Trustees of the British Museum].

- Timothy Clayton, ‘Bowles family (per. c.1690–c.1830)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008.

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2, 13 June 2016), October 1730, trial of Margaret Eaton , alias Irish Peg (t17301014-76).

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2, 13 June 2016), December 1740, trial of Margaret Poland , alias Irish Peg (t17401204-51).

- ‘Country News’, Whitehall Evening Post (28 March 1747); Issue 176. 17th-18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers.

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2, 13 June 2016), September 1815, trial of THOMAS STEVENS (t18150913-181).

- Janice Turner, ‘Ill Favoured Sluts: The Women of Rosemary Lane’, An Anatomy of a ‘Disorderly’ Neighbourhood: Rosemary Lane and Rag Fair, c. 1690-1765 , pp. 283-284 [PhD Thesis, 2014].