If you’ve ever studied the Irish in eighteenth or nineteenth-century London, you’ve probably quickly learned that they were clustered in the Rookery – the twisting streets and narrow lanes, of St Giles-in-the-Fields. In the eighteenth century, St Giles was one of the relatively newly built regions of the metropolis. During the Tudor and Stuart eras, ‘London’ had distinctly meant the medieval walled ‘City of London’ along the north Bank of the Thames. Across the river was another urban area: Southwark, or the ‘Borough’, which was accessible via London Bridge. And to the west where St Giles now stands, was fields separating London from Westminster up river a few miles. Over the course of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, the fields filled in with houses and new streets, in large part to manage the demand for housing arising from the metropolis’s thousands of migrants arriving each year.

For ‘Londoners’ – that is, people from the ‘City’, there was a clear hierarchy. These ‘extra-mural’ or beyond-the-walls parishes were not part of their London. When you look at the Irish in London, you’re almost exclusively looking at this ring of parishes outside of the city’s walls. It was a space people could grow into, of which St Giles was most-well known for its Irish population.

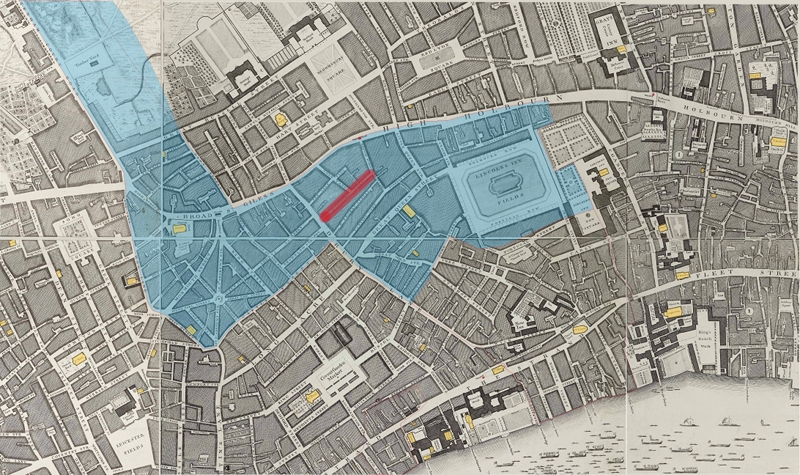

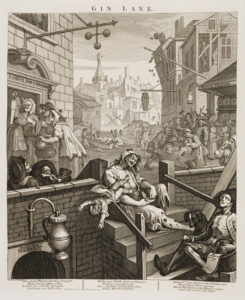

I had always assumed that the core of the Irish community was in 7-dials, the network of converging streets in the south-west corner of the parish which spread out like a web from a central plaza (see the map at the top of the post). Today it’s not a bad place to go to buy some shoes or have a nice meal, but in the eighteenth century, it was a centre of poverty and squalor. Nearby Hog Lane which forms part of the parish’s western boundary, was the inspiration and setting of Hogarth’s ‘Gin Lane’.

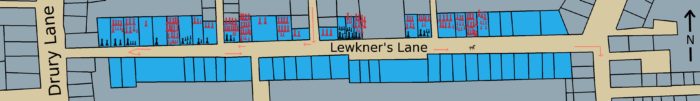

As it happens, I was wrong. The centre of Irish London seems instead to be a few streets to the east, in Lewkner Lane (now Macklin Street). In 1767, at the request of the Bishop of London, the local curate, Richard Southgate, conducted a census of Catholics in his parish.[1] St Giles wasn’t being singled out; this was part of a national endeavour by the Church of England to better understand the ‘Visible Increase of Papists in the Cities of London and Westminster’.[2]

All parishes under the Bishop’s jurisdiction were required to submit a census of ‘Papists’ (Catholics) in their neighbourhood, along with details of their names, occupations, ages, and their length of residence. Southgate did not adhere to the instructions, and instead he produced a street-by-street account of Catholic householders and lodgers. We have no names, but we know where in the parish they lived, giving us a unique insight into Catholic housing in one small part of London. From that census, it’s the modest Lewkner Lane, a narrow street only 180m long, that stands out as the most Catholic, with 202 individuals in the street’s 57 buildings.

How did 202 Catholics end up on Lewkner’s Lane? It’s difficult to tell, but I suspect it’s down in part to the letting strategies of the landlord. We don’t know who owned the houses on Lewkner’s Lane, but running parallel, a Joseph King leased a ‘large portion of the property’ in St Thomas Street immediately to the south (a.k.a. King Street) in 1765, and despite being the same size as its neighbour, was home to only 28 Catholics – 14% the number in Lewkner’s Lane.[4]

It’s unlikely that the superior landlord managed the short-term requests for lodgings from temporary people looking for a place to lay their heads, but someone like him almost certanily decided who to let the main house to, who may have had the right to rent out the other rooms. An Irish family downstairs looks like it might have increased the chances of Irish families upstairs, as well. The eighteenth century certainly offered no protection against religious discrimination, and so an Irish Catholic looking for a room was at the mercy of those with the ability to grant or refuse that access. Getting to the core of the matter will require some more digging, but given the very recent ‘Brexit’ vote here in England, fueled in part by concerns over migration, it’s more important than ever to understand how these ethnic communities affected the social dynamics of cities such as London.

It’s also a good opportunity to understand how spaces like St Giles and Lewkner’s lane ceased to be ‘Irish’ or ‘Catholic’ spaces, and just became London.

Footnotes:

[1] FP Terrick, 23, ff. 20-27. Lambeth Palace Library (1767).

[2] FP Terrick, 20, ff. 1. Lambeth Palace Library (1765).

[3] Base map from: Nathaniel Rodgers Hewitt, ‘Plan of the parishes or divisions of St Giles and St George, Bloomsbury’ (1815): [http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/crace/p/007zzz000000015u00002000.html]

[4] ‘Site of Rose Field: Macklin St., Shelton St., Newton St. (part) and Parker St. (part)’, in Survey of London: Volume 5, St Giles-in-The-Fields, Pt II, ed. W Edward Riley and Laurence Gomme (London, 1914), pp. 27-32. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol5/pt2/pp27-32 [accessed 10 July 2016].