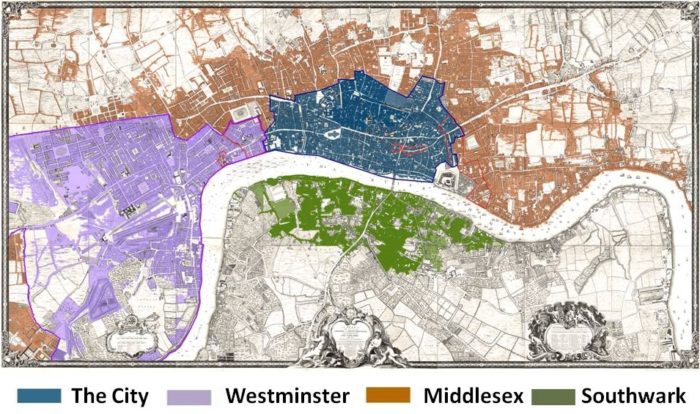

As outlined in ‘Loose, Idle and Disorderly’,[2] the county of Middlesex hired a man named Henry Adams to shepherd all of the county’s vagrants to the edge of the county so they could be sent on their way. This meant that at least three different systems were feeding vagrants into Henry Adams’ hands.

1) Those proclaimed vagrants in the ‘City’ and passed directly to Adams (blue).

2) Those proclaimed vagrants in the Liberty of Westminster and processed via Tothill Fields prison (purple).

3) Those proclaimed vagrants in urban Middlesex and processed via Clerkenwell prison (rust).

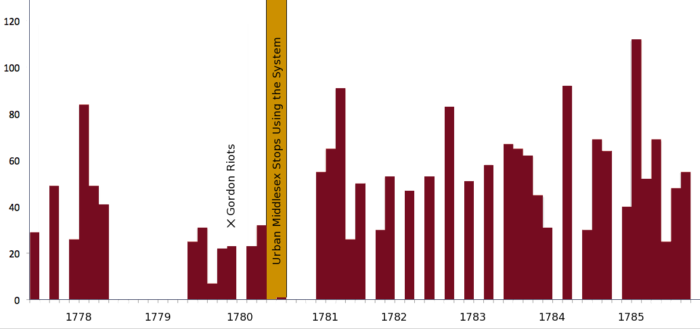

The lists that Adams submitted eight times per year to the county in exchange for payment have formed the basis of our ‘Vagrant Lives’ dataset of 14,789 individuals removed via this system. The lists were produced by Adams as a bill to the county, so he had every reason to ensure everyone he conveyed in his cart was included on the lists. That’s why it was so surprising to discover that between at least 7 December 1780 and 22 February 1781 only a single vagrant was expelled from Urban Middlesex (see Gold section on Figure 2). That vagrant was a man named Bryan Lyons, who was condemned by magistrate John Bretell and sent home to Warwickshire after a short stay in Clerkenwell.

Tim Hitchcock has highlighted what he calls the ‘London Vagrancy Crisis’ of the 1780s, during which London’s gaols were attacked (during the Gordon riots) and otherwise under intense pressure as they had not been designed for long-term incarceration.[3] Instead, the practice had long been to send criminals abroad, but the loss of the American colonies denied that option until the first penal colony was established in Australia in 1788. In the interim, London’s gaols were overflowing, causing unrest.

It’s quite likely that vagrancy had to take a back seat for a few months as the magistrates and gaolors dealt with bigger problems. Why Westminster didn’t have the same problem, we cannot be sure. Because of missing records, we can’t even be certain how long it lasted, as we do not have the three lists that should follow this. By mid-1781 however, the vagrants have returned to Henry Adams’ hands.

This anomaly in our records demonstrates that local administration is incredibly complex.[4] Understanding how systems like vagrancy removal worked involves an awareness of that complexity, and a keen eye for strange anomalies in the source base.

Footnotes:

[1] Hitchcock, T., et al. ‘The City of London is indicated in dark blue, Westminster in purple, Middlesex in brown, and Southwark in green…’ London Lives (2012) [https://www.londonlives.org/static/WestminsterLocalGovernment.jsp].

[2] Crymble, A, Falcini, L and Hitchcock, T 2015 Vagrant Lives: 14,789 Vagrants Processed by the County of Middlesex, 1777–1786. Journal of Open Humanities Data 1:e1, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/johd.1

[3] Hitchcock, T. ‘The London Vagrancy Crisis of the 1780s’, Rural History, vol. 24(1) (2013), 55-66.

[4] See: Hithcock, T. & Shoemaker, R. ‘The state in chaos: 1776-1789’, London Lives: Poverty, Crime and the Making of a Modern City, 1690-1800, (2015) pp.333-393.